In my last post, ‘Does sleep have a history?,’ I set out some of the lessons that history can offer about how sleeping habits and sleep-quality are shaped by the societies, cultures and environments in which we live. Sleep’s importance to physical and mental health has been recognised by most individuals and societies throughout history but there are important variations in how this essential period of rest was believed to affect body and mind, and consequently, in the time and resources that have been dedicated to the pursuit of peaceful slumber. Changing ideas about sleep’s purpose and its relationship to human health are thus central to its daily experience.

In early modern England (the focus of my current research), the widespread practice of bi-phasic, or ‘segmented’ sleep, has captured most media attention to date. This refers to the habit of sleeping in two separate cycles during the night, rather than in one consolidated sleep-cycle of 7-8 hours, which people called their ‘first sleep’ and ‘second sleep’ (Ekirch, 2001). On 31 January 2016, the psychologist Richard Wiseman, even encouraged readers of The Guardian to ‘consider segmented sleep’ if they were having trouble dropping off at night. Whilst segmented sleep has been singled out for special notice, it is worth noting that early modern sleeping habits of many different kinds formed the bedrock of a rich, holistic culture of preventative healthcare that was designed to safeguard the long-term health of body and mind.

We all know the delightful moods and sensations that sound sleep can bring, and we miss them when we are sleep-deprived, or forced out of bed too soon to go to work, comfort a crying baby, or dash to the airport to catch an early morning flight. The grumpiness associated with the phrase ‘getting up on the wrong side of the bed’ neatly conveys the negative effects that too little, or poor-quality sleep, can have on our bodies, minds and moods. Today, we have a sophisticated set of medical explanations to pinpoint exactly why we feel out of sorts – irritable, hungry and lacking in energy – when we don’t get enough sleep. These feelings and sensations were just as familiar however to people in the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, who had their own set of bodily gestures and expressions to describe them.

‘Getting up on the wrong side of the bed’ was in fact a well known early modern phrase and its etymology opens a window onto the influential body of healthcare knowledge known as the ‘six non-natural things’, which was central to the way that people thought about sleep and how they practiced it. The main ambition of this system of healthcare, which was based on the medical wisdom of the ancient world, was to preserve human health in harmony with the natural environment. The body’s four humours (blood, choler, melancholy and phlegm) were kept in balance by paying careful attention to the six non-natural things – a set of environmental and dietary rules that related to fresh air, food and drink, sleeping and waking, motion and rest, excretion and retention, and the passions of the soul. A healthy and long life depended on the individual’s careful management of all six categories. Regular habits of sleeping and waking kept the humours in check and prevented their corruption, which warded off disease. In 1539, Sir Thomas Elyot, the lawyer, humanist scholar and ambassador to King Henry VIII, spoke for many when he stated that perfect sleep made ‘the body fatter, the mynde more quiete and clere’ and ‘the humours temperate’. Elyot offered this advice to a large audience of readers in his best-selling healthcare guide The Castel of Helth and his words were echoed in different forms and formats well into the eighteenth century.

As well as supporting overall good health, a sound night’s sleep had a more specific function in supporting the process of digestion, which shaped a range of distinctive sleep-related activities. Chief among them was adopting the correct sleep posture at bedtime. Most healthcare guides (also known as regimens of health) advised people to sleep ‘well bolstered up’, or with their heads slightly raised with the aid of a pillow or bolster. The gentle slope that this position created between the head and stomach was believed to speed the process of digestion and to prevent food being regurgitated during the night. It was just as important for sleepers to rest first on their right side of their bodies, before turning onto their left side during the second half of the night. Resting first on the right, which was judged to be hotter than the left side of the body, allowed food to descend more easily to the pit of the stomach, where it was heated during the initial stage of digestion. Turning onto the cooler left side of the body after a few hours released the stomach vapours that had accumulated on the right and spread the heat more evenly through the body.

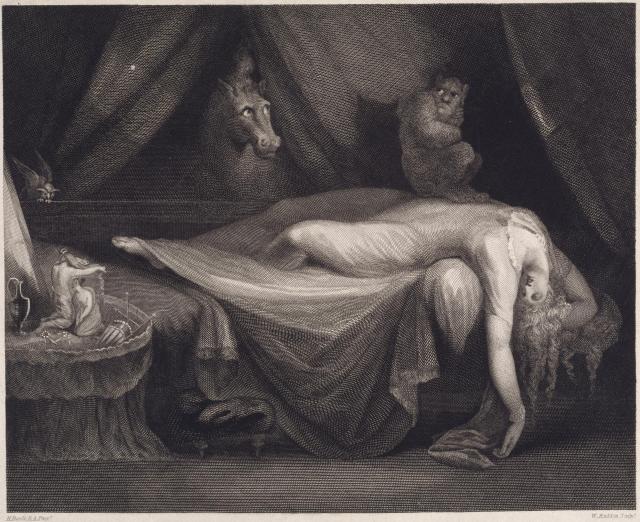

References to sleep posture were rarely worthy of note in personal diaries or letters but English folk beliefs suggest that there was a widespread perception of a right and a wrong way to lie in bed, and to rise from it. Rising on the right side of the bed was considered by some to be an unlucky omen for the day ahead. In an astrological text of 1652, the Church of England clergyman John Gaule judged it folly ‘to bode good or bad luck, fortune [or] successe, from the rising up on the right, or left side’. Despite Gaule’s objections, this seems to have been a familiar saying, with obvious links to healthcare knowledge. Since physicians encouraged sleepers to spend the second part of the night on their left side, rising on the right may suggest that body and mind were disordered by a failure to heed this advice. Even more dangerous than sleeping on the wrong side of the body, was sleeping flat on the back, which was believed to flood the base of the brain with excessive moisture, trigger nightmares, invite the visit of an evil spirit known as the ‘incubus’, or even to herald the sleeper’s early death. Early modern people took great care to moderate their bedtimes, and manage their sleeping environments, and they may well have been similarly diligent about their sleep-posture to increase their chances of resting well and securing their wellbeing. These intricate daily habits reveal the high value that was attached to sound sleep, which was encouraged by the long-term preventative culture of healthcare that characterised this period.

‘The Nightmare’ (London, 1827) © Victoria and Albert Museum, London