In my last post ‘Sleep, Health and History’ I described the importance of healthy sleep to the long-term health of body and mind within early modern medical culture. Sleep was an essential restorative of health but it was also a time of vulnerability and danger where natural and supernatural threats had to be countered. These understandings were the key drivers of sleeping habits and of the cleansing regimes that centred on and around the bed. The bedstead’s wooden frame, its layers of mattresses, bolsters and textiles usually accounted for one-third of the average household’s assets. This high economic value was matched by the practical and symbolic importance of sleep’s apparatus within the home. The bed’s material and emotional significance in relation to household formation, love and marriage has been explored by Joanne Bailey and Angela McShane, but its make-up and management also reveal the unrivalled importance of these materials as guardians of sound sleep.

Diaries, letters, household accounts and receipt books document the exhaustive efforts that people made to sleep in clean, safe and airy environments. Nowhere else in the home was so heavily governed by rules of hygiene and cleansing regimes, which ranged from the beating and turning of mattresses to sprinkling rose petals on the bed’s sheets. Persistent battles were fought against bed-bugs, which regularly infested old wooden bedsteads. Hannah Glasse’s (1760) included no less than eight receipts for keeping bedsteads free from flies, fleas, bed bugs, gnats and silkworms. The hot summer months posed particular difficulties for controlling bug infestations. At this time of year Glasse advised people to place a garland of ‘Ash-boughs and Flowers’ at the bed’s head, which formed ‘a pretty Ornament’ and whose floral scent attracted flies and gnats away from the sleeper’s body. Those who lived in marshy or fenny areas might burn a piece of fern in the chamber or hang pieces of cow dung at the foot of the bedstead to keep bugs at bay. Country-dwellers were directed to bathe their hands and face in a mixture of wormwood, rue and water before retiring to bed. These parts of the body, which lay unprotected by bed-sheets and bedclothes, required additional protection.

The impulse to sleep in safety and protection extended to the bed’s textiles and it had a powerful effect on the senses. Linen was by far the most popular material for bed-sheets in seventeenth and eighteenth-century England and it varied widely in its quality, cost and availability. Whilst some were able to manufacture their own sheets by growing and spinning flax, others could purchase high-quality linen such as ‘Holland’, which was named after its place of origin. Linen sheets were prized for their cool and crisp sensations, which were believed to regulate the heat of the body’s internal organs, to absorb the its nocturnal excretions and to close its pores against dangerous pollutants in the night air. These qualities complemented the healthcare principles of the six non-naturals that governed people’s attitudes towards sleep and they also helped to foster strong attachments between individuals and their bedding materials. It was a common practice for people to take their own bed-sheets with them when they travelled. This reduced the risk of having to sleep beneath unclean sheets but it also promoted familiar scents and sensations at bedtime, which helped to offset the feelings of vulnerability that were associated with sleeping in alien environments.

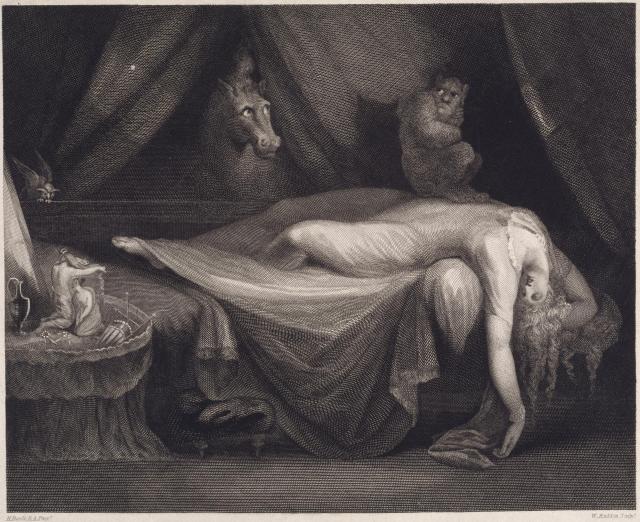

For some people, the physical and psychological protection offered by bed-sheets went far beyond the natural world and offered a tangible defence against diabolical attack. When John Wesley’s family home in Epworth, Lincolnshire, was invaded by the malevolent spirit known as ‘Old Jeffrey’ in the winter of 1716-17, his sister Molly dived beneath her bed-covers for protection when she heard the latch of her chamber door rattling at bedtime. Molly’s sisters Suky and Emily also buried themselves under their bed-sheets when they heard Old Jeffrey’s familiar knock after their father Samuel had shut them in for the night. Since sleep was widely understood as a time of slippage between the natural and supernatural realms (as shown in Young Bateman’s Ghost), it seemed logical to some that bed-sheets might save them from natural and diabolical threats. The power invested in these materials was likely strengthened by the broader uses of textiles like linen, which were used to make clerical vestments and to wrap dead bodies before burial.

Efforts to control sleep’s material environments took many different forms but they collectively underline the feelings of vulnerability and danger that sleep generated. The cleansing rituals that surrounded the bed and the careful choice of its textiles were tokens of household decency but they were also effective methods of safeguarding body and soul and thus of easing anxieties at bedtime.

Young Bateman’s ghost, or, a godly warning to all maidens (London, 1760) courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University